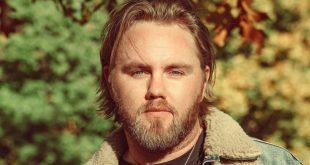

Folk singer-songwriter Abigail Dowd is a child of the South who ventured to Florence, Italy, then Maine, in search of how she fit into the world — eventually ending up right where she started with an understanding that, sometimes, all any of us needs or wants is to feel heard and seen. Written with a new realization of the separation between herself and her experiences, Dowd’s new album Not What I Seem spans songs that tell her story of finding forgiveness, healing, and even gratitude, for all that has shaped her. The album will be released April 5. The first single, “Chosin,” just premiered. Listen here.

On Not What I Seem, Dowd steps through the looking-glass of not just her own story, but others’, as well. Throughout this song cycle, Dowd learns to stand back and see life as a work of art, as a collection of stories that can be re-written and let go. Growing up in Southern Pines, North Carolina, Dowd soaked up both her family’s musical loves and her neighbors’ hard-scrabble lives. She absorbed Tracy Chapman, Jim Croce, and Tchaikovsky, while experiences of emotional and environmental devastation embedded themselves on her psyche.

In the haunting title track, inspired by her life as an artist’s model for 10 years, Dowd casts off the assumptions about who she is so that she might finally know, leaving behind the expectations of another. It’s a representation of the album’s journey as a whole, as she examines how the cloudy visions of others can infiltrate self-worth. Through its notes, she leaves behind the things she isn’t and re-writes her own story. Later, one of the most potent moments of the album is contained in the defiant personal reckoning that is “Old White House.” Dowd’s subconscious mind was able to bypass the pain of a childhood experience and finally let it go. Paired on the album and in their themes, “Goodbye Hometown” and “Oh 95” are two sides of the same leaving home coin — one depicting her departure, one recounting return.

Inspired by her grandfather who fought in the Battle of Chosin Reservoir in the Korean War, “Chosin” examines the ways generational wounds can be passed down. The song details the ways war changes people and finds parallels between her own inner battles and those that were brought home from the battlefield.

In the rough-hewn “Wiregrasser,” Dowd recounts the tale of the longleaf pines through the perspective of an Alabamian turpentine worker, who both depended on his job and the diverse longleaf pine ecosystem that was being decimated by the turpentine industry for his survival. With its steady, smoldering chug, “Desire” was sparked by a conversation Dowd had with her brother, a fireman, about the physical, mental and emotional challenges that come with the job. The breezy folk of “The Other Side” offers advice to a friend who needs to take a different tack.

By sharing these parts of herself, Dowd lets them go. “Until we can tell our stories and be heard, we hold on to them, and bury them and get really fond of them. They come to own us,” she says.

The letting go, however, gave her yet another gift. There was forgiveness, to be sure, but then there was freedom.